Aaaaand we’re back. Please excuse the break – life very much got in the way and trust me, taking a break was way better than the schlock I would have been churning out if I’d forced myself to post every day. Then again, maybe this is schlock too. You’ll have to be the judge, dear reader.

Anyway. Onward.

A couple of weeks ago, over drinks with a friend and fellow design professional, the talk turned to the topic of futurists. I have, on occasion, been called a futurist by well-meaning people trying to describe what I do. It usually takes me several seconds to breathe and remind myself that they don’t mean it as an insult before I can smile and gently steer the conversation in more productive directions.

So what’s my problem with futurists? It’s that many of them (not all – I have met some notable exceptions, who are brilliant, insightful and super-fun individuals) are shysters. Even the futurists I know and love don’t like calling themselves futurists, but it’s what they do. I also do other things – product design and organisational strategy, business models and branding – so I can weasel my way out of the moniker. It’s just a shame that I’d want to. Here’s Wikipedia’s definition:

“The term “futurist” most commonly refers to authors, consultants, organizational leaders and others who engage in interdisciplinary and systems thinking to advise private and public organizations on such matters as diverse global trends, possible scenarios, emerging market opportunities and risk management.”

Yep, that’s a lot of what I do. Systems thinking, as you may have noticed, is kind of A Thing for me. However, this is AOL’s definition of a futurist:

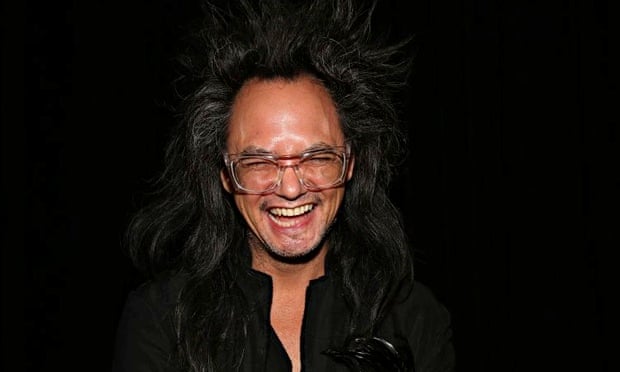

Shingy, AOL’s ‘Digital Prophet’. Photo from this Guardian article.

It’s not just his haircut that bothers me. It’s his vapidity. I totally get that it’s important for big companies to have help staying abreast of what’s new and what’s next. I guess I just think there should be more to it than the superficial. Granted, the Guardian and New Yorker pieces aren’t exactly the nicest profiles I’ve ever read, but I’ve heard far worse. Shingy might be an idea man, but that’s all he is.

There’s a curious thing that happens in corporate board rooms. I’ve witnessed this a fair few times: some external speaker or consultant comes in and gives a talk. Nobody in the room can make sense of it, so nobody asks any questions. Later, once the speaker has left, most of the people who saw the talk ask each other what they thought. Usually the consensus is that it was brilliant. This is because nobody wants to be the idiot who didn’t get it. Nobody wants to look stupid next to their peers and colleagues. So the speaker, instead of being called out for spouting complete and utter nonsense, gains a reputation as a mind-boggling genius and ups their rates.

We love great ideas and the people who have them. Da Vinci, Newton, Edison, Tesla, Torvald, Musk – these are our folk heroes. The problem is that there is a difference between having an idea and making something of it – assuming it’s even a good idea in the first place. Have a look at how many of the aforementioned inventors’ ideas failed abjectly and you’ll see that not every idea is good, and usually the idea itself isn’t enough; you’ve got to have an understanding of how it fits into the bigger picture in order to make something valuable of it.

And sexiness isn’t necessarily a gauge of quality, no matter what TED talks might lead you to believe. Sometimes small ideas, small changes, can have massive impact in unforeseen ways. But over the past decade or so, the startup-fuelled echo chamber of technological genius has built up this fallacy that the idea is all that matters. I suspect this underlies a lot of the startup world’s reluctance to engage with some of the more complex issues around their ideas (social impact, sustainable commercial value, etc.).

I’ve written before that when it comes to technology, we tend to equate progress with convenience. When it comes to personal success, we tend to equate progress with money, or fame (with the assumption that money will follow). And fame – outside of certain scientific and philosophical communities – is not predicated on depth or rigour of thought. So, in a completely incomprehensible turn of events, at one point a few years ago we decided that just being a celebrity somehow entitled one to have influence in the tech landscape. Alicia Keys was made Creative Director of Blackberry. Lady Gaga designed a product for Polaroid. And who can forget will.i.am’s brilliant contribution to the world of branding? I’m not saying that branding consultants need PhDs in linguistics, but do you really want to take typography advice from a man who clearly does not realise that Devanagari script is used to write Hindi?

Maybe it’s comforting to think that the future (or even the present) of technology is straightforward enough to explain in 18 minutes or a quick set of sketches. But it’s not true. And these false prophets do far more damage than many people realise. When companies, especially large companies with big budgets and lots of influence, follow superficial guidance without thought to the longer-term repercussions, bad things can happen. And it’s us – the people at the other end – who feel the effects.

It is important, vitally so, to think about the future and where we’re all going. It’s also important for all of us living in the present to think a bit more critically about the ‘futures’ we hear about on (internet) TV.